This is a companion to a previous post: From train to tree: Golden Gai, Toden streetcar, and Shinjuku Promenade Park

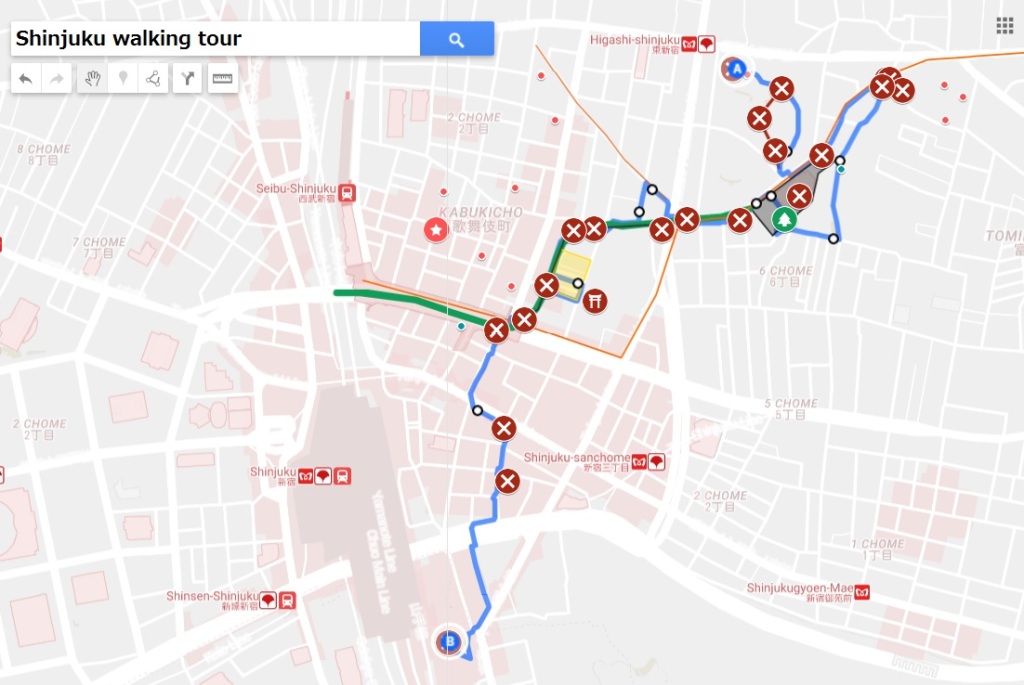

Here’s a map of the walking tour described in this post (see bottom for interactive map):

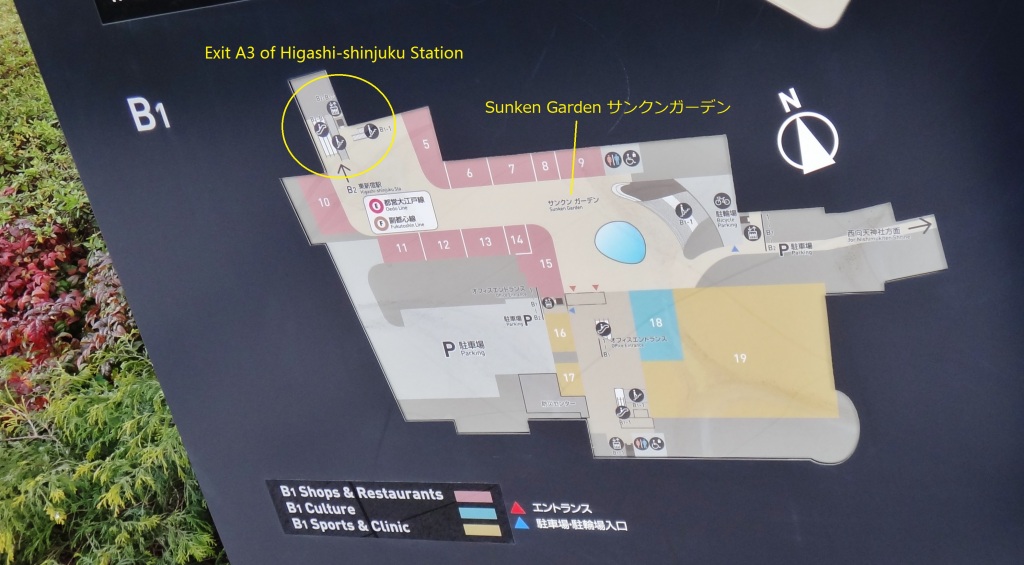

We start the day at Shinjuku Eastside Square 新宿イーストサイドスクエア, a large office and retail complex on the edge of Kabukicho (map):

(1) Higashi-shinjuku Station, Exit A3

Shinjuku Eastside Square sits at the top of Exit A3 of Higashi-shinjuku Station 東新宿駅 (Fukutoshin Line and Oedo Line). The escalator ride offers a dramatic first view of the building’s glass and stone exterior.

We are now in the Sunken Garden サンクンガーデン, an open-air collection of shops and restaurants surrounded by overhanging, Gaudi-esque walls. We’re on the north side of the building, in complete shade, which deepens the feeling of being in a basement or cave.

Look up, it’s an imposing building:

The facade is an interesting mix of stone and raised glass panels:

(2) Plaza on north side of Shinjuku Eastside Square

Directly above the sunken garden is the building’s ground-level park/plaza. This space has a mildly unfriendly atmosphere; first, the building looms above you, literally blotting out the sun; second, the surface is primarily covered by stone, with large holes in the ground that look down at the sunken garden. Finally, although there is grass, it is roped off. This space feels less like a park than the lawn of an American office park.

The amphitheater, and looking down at the water feature:

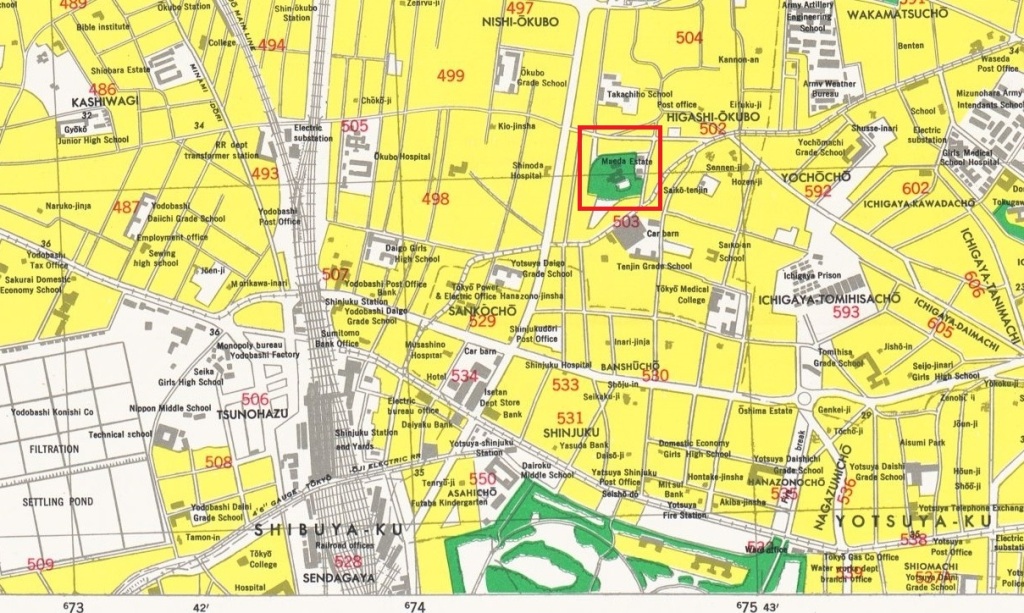

As for any large building in Tokyo, the natural question is: how did this get built? The process of acquiring land can be very time consuming; a well known example is Roppongi Hills, for which land acquisition took 14-17 years (reference; see case study, PDF). For Roppongi Hills, the land came from 400 smaller lots. In contrast, Shinjuku Eastside Square is built on a much smaller number of lots. As recently as 1945, this plot of land was the Maeda Estate 前田公爵邸, as seen here in a map and aerial photo from 1945/50:

Some time after the war the Maeda Estate was turned into the Nippon Television Golf Garden 日本テレビゴルフガーデン, seen here in 1974/78:

For aesthetic purposes, old maps of the area have been etched into the ground; although not labeled, the following map appears to be centered around the Maeda Estate. There are also thumb-shaped pieces of metal embedded in the sidewalk that curves around the east side of the building. Are these acorns?

For context, here’s a street map, several years old. In addition to the old Maeda Estate land, I’ve made note of Shinjuku Promenade Park, which is discussed later in this post.

(3) Inside Shinjuku Eastside Square

A quick peek inside shows us more curved, Gaudi-esque columns coupled with the dark glass typical of contemporary Tokyo office buildings.

(4) South side of Shinjuku Eastside Square

The south side of the building feels far friendlier due to the southern exposure. Perhaps the only shop on this side of the building is an egg-ish building called Artnia アルトニア.

(5) Shinjuku Cultural Center 新宿文化センター (former streetcar train shed)

Immediately to the south of Shinjuku Eastside Square is the Shinjuku Cultural Center 新宿文化センター, built on the site of the old Okubo Garage 都電大久保車庫, a train shed for line 13 of the Tokyo Toden 東京都電 streetcar.

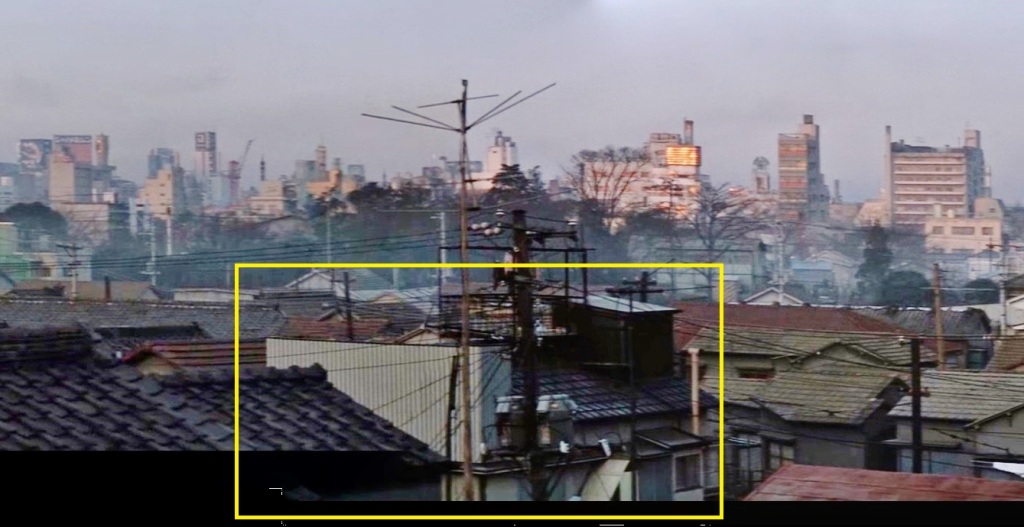

Most of the subsequent pictures are from the 1968 yakuza film, Outlaw: Gangster VIP 「無頼」より 大幹部, which I referenced in a previous post.

Location 5.1:

The old Okubo Garage can be seen in the photo, below left; its location is indicated in an aerial photo from 1961/64.

Location 5.2:

This panorama from the film, facing southwest, shows the Toden streetcar tracks at right, and a building at left, which we will revisit shortly. This is followed by a photo of the location today.

Location 5.3:

In the same location as 5.2, but now facing north, we see the Toden tracks and a low underpass, which still exists:

Location 5.4:

The building mentioned at location 5.2 is shown in greater detail below, plus views of the building’s side alley:

The same location today:

Location 5.5:

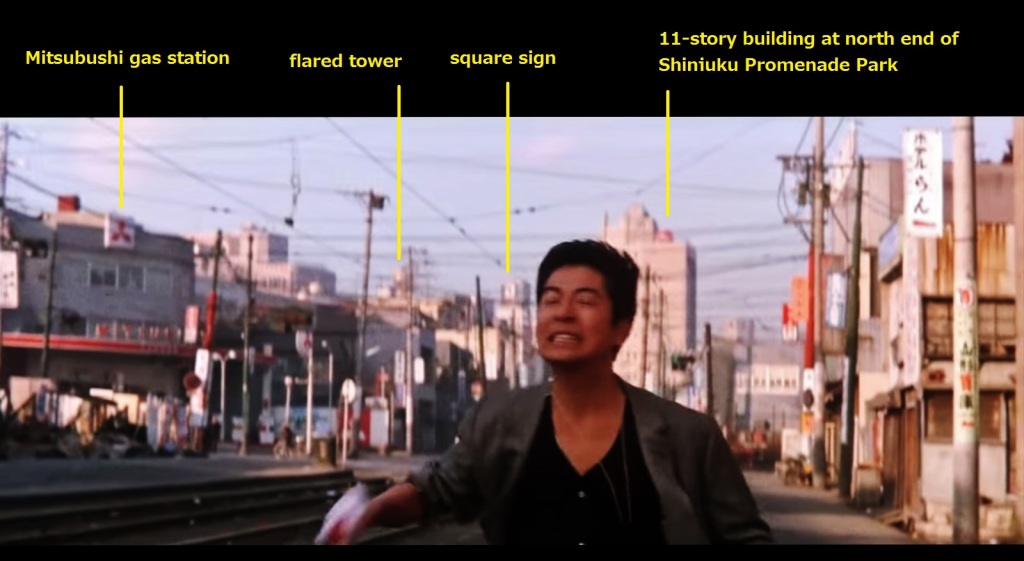

The following panorama from the film was taken either from the window of a house or from the small rise behind the buildings. The annotations refer to structures in the Shinjuku station area that are visible in other photographs from the era.

Here’s a photo from roughly the same location today:

(6) An introduction to kanban kenchiku (billboard architecture)

Kanban kenchiku 看板建築 is a form of vernacular Japanese architecture in which a flat, quasi “Western” facade hide a more traditional Japanese structure. This style can be clearly understood by looking at picture of billboard architecture toys and scale models, such as this:

Example 6.1:

Example 6.1:

Just across the street from the old house in the Goro film is a typical example of kanban kenchiku, visible obliquely in the Goro film:

The same buildings appears to exist today:

Example 6.2:

There’s another cluster of kanban kenchiku buildings, though these structures are less obvious examples. Also of note: the wide sidewalk in front of the buildings is the result of the old streetcar line.

(7) Mitsubishi gas station

View of the Mitsubishi gas station and Toden line streetcar tracks in 1968, compared with the same view from today. (Photo location, 7.1, facing west).

(8) Shinjuku Promenade Park 「新宿遊歩道公園四季の道」 and Golden Gai 新宿ゴールデン街

The most exciting transformation of the former streetcar tracks is a section now known as Shinjuku Promenade Park 「新宿遊歩道公園四季の道」, a tree-lined boardwalk and paved path that runs next to the Golden Gai bar district.

Example 8.1:

Facing south/southwest, then and now:

Example 8.2:

Facing northeast, then and now:

Example 8.3:

Facing north, then and now:

Example 8.4:

Sign at the entrance of Shinjuku Promenade Park 「新宿遊歩道公園四季の道」, and view of the park from across the street:

A map of the Golden Gai bar district, circa 1979. The Golden Gai district is crowded, dingy, and a fire hazard. Yet it has historic charm, and provides a psycholigical link to Shinjuku’s post-war black market, which was built next to the Yamanote line tracks, nearby.

(9) Shinjuku streets in the 1950s and 1960s

Example 9.1:

This photo is taken somewhere to the west of Golden Gai, facing west The Yamanote line tracks are visible, along with a sign with the encircled kanji 緑屋, with 「ミドリヤ」 written below; this was Midoriya Shinjuku みどりや 新宿 / 「ホームビルの緑屋」 “Green shop home building.”

Example 9.2:

Ohdori Boulevard 新宿大通り, in front of Mitsukoshi, facing west, 1953 (source):

And a panoramic photo taken from the rooftop of Mitsukoshi, circa 1952-1955 (source):

(10) Fugetsudo cafe 風月堂 (Fūgetsudō ふうげつどう)

From 1946 to 1973, Fugetsudo 風月堂 cafe was an integral part of the Shinjuku arts scene, drawing such luminaries as Beat Takeshi ビートたけし, Taro Okamoto 岡本太郎, Tadao Ando 安藤忠雄, and Shuji Terayama 寺山修司. This quote by the poet and photographer Gōzō Yoshimasu 吉増剛造 sets the scene (from Radicals And Realists in the Japanese Nonverbal Arts: The Avant-garde Rejection of Modernism):

The exterior and interior of the building was quite striking:

Here’s a description from the excellent book review: Angela Carter in Japan, by Edmund Gordon, about Angela Carter’s experiences in Tokyo in 1969:

“As she came to understand the city’s scrambled topography, she gravitated towards Shinjuku, and the pleasure district of Kabukicho, a lurid stretch of bars, dance halls, coffee houses and hostess clubs, haunted by artists and students, and anyone else who valued cheap entertainment and easy encounters with strangers (“kind of Greenwich Village” was how Angela explained it to friends in England). She began “spending most of [her] time in coffee shops listening to modern jazz on the stereo”. Her favourite was the Fugetsudo, a traditional wooden building spread across two floors and entered via a lanterned doorway off a narrow alley, with an atmosphere that she described as “hashish-dream somnolence”. It was a magnet for Western backpackers – many arrived there directly from the airport – and the preponderance of white women made it, in turn, a magnet for local men.”

The Greenwich Village comment is not unique; in conjunction with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, foreigners read about Fugetsudo in a pamphlet titled “Japan’s Greenwich Village” 「日本のグリニッジ・ヴィレッジ 」.

So where was Fugetsudo located? It seems that the cafe used to be at the current location of the IDC Otsuka Kagu furniture showroom; this building used to be the Shinjuku Mitsukoshi South Annex 新宿三越の南館 / 三越南館裏. The location is noted on a blog that includes the above map. Additionally, the side of the current building has the following plaque (source):

The plaque mentions a company called 株式会社風月堂, which is Fugetsudo Kabushiki gaisha (which basically means Fugetsudo, Incorporated). Searches for 株式会社風月堂 link to a Fugetsudo sweets company from Kagoshima (website). There are other Fugetsudo sweets companies in Tokyo, so I’m can’t say with certainty whether the Fugetsudo Shinjuku cafe was associated with the Kagoshima company.

Interactive map:

Links:

Streetcars

- Tokyo Streetcar maps

- 都電が走ってた緑道~新宿篇~ (includes map of the Shinjuku Line 13)

Black markets

- Ikebukuro’s yami-ichi (post-war black market), in miniature

- Black Market Phantom Guidebook ヤミ市幻のガイドブック」

- Other black markets: http://shomon.livedoor.biz/archives/52235325.html

- Excellent photos of post-war black market 闇市 (broken link: officej1 com/trade/omoi49 htm)

Shinjuku Historical Photos

Fugetsudo:

- Fugetsudo Wikipedia (Japanese)

- Background on Goro Yokoyama 横山五郎, the founder of Fugetsudo Shinjuku

- Photos: 新宿風月堂(喫茶:1946年~1973年8月31日) Shinjuku Fugetsudo (Coffee: 1946 – August 31, 1973)

- Review of book on Shinjuku culture: 「新宿考現学」 深作光貞 1968 “Shinjuku Arts & Crafts” / Shinjuku Kōgengaku , by Mitsunori Fuka 1968; available here

- Interview with Akihiro Miwa 美輪明宏, who makes reference to the good ‘ol days in Shinjuku and at Fugetsudo, with mention of Beat Takashi: click here for interview

- ☆今は無き 『新宿風月堂』 ☆ There is not now “Shinjuku Fugetsudo”; broken link: blogs yahoo co jp/julywind727/33250491 html

- Place(場所の記憶) 新宿風月堂(喫茶) Place (Memory of place) Shinjuku Fugetsudo (cafe) – broken link: officej1 com/70avna_gard/Place htm

- 新宿風月堂(店内) Shinjuku Fugetsudo (inside)

- Location: びーとたけしの新宿を歩く Walk the Shinjuku of Beat Takeshi

- Reference to a concert by ‘Toshi Ichiyanagi & Group Ongaku‘, circa 1961, at “Fugetsudo Hall”, and the so-called “John Cage shock“

- “Tokyo, 1955-1970: A New Avant-garde” includes the opening of Fugetsudo as a key Tokyo transformation. It mentions the Painting and Sculpture Exhibition (Kaiga to chōkoku-ten) 絵画と彫刻展, hosted by art critic Egawa Kazuhiko 江川和彦 (1896-1981).

- One artist whose work was exhibited at Fugetsudo during this era was Yamaguchi Katsuhiro 山口勝弘; his website includes the following group exhibition listing: 1957 「新しい視覚と空間をたのしむ夏のエキジビション」風月堂,東京 (1957 “Summer Exhibit by Members of Experimental Workshop,” Shinjuku Fugetsudo, Tokyo); see also:

- Katsuhiro Yamaguchi: Interview; EVERY FUTURE LEADS TO ITS OWN PAST, by Andrew Maerkle and Natsuko Odate

- 1974-1975 Las Meninas, Yamaguchi Katsuhiro Archive

- Katsuhiro Yamaguchi: Imaginarium

- Another artist who exhibited at Fugetsudo (reference is made to 1957): Toshiyuki Tanaka 田中稔之, a member of the 行動美術協会 (Behavior Art Association)

Greenich Villages of Tokyo, in today’s Tokyo

- Splitting a Hip Neighborhood, in More Ways Than One (New York Times)

- Shimokitazawa: Tokyo’s Greenwich Village; broken link: wayfaringminimalist com/shimokitazawa-tokyos-greenwich-village/

- Greenwich Village of Tokyo, Nakameguro

Nearby items of interest:

- (A) TULLY’S COFFEE (at top of exit A3)

- (B) Senpukuji 専福寺

- (C) Sennenji 専念寺

- (D) Hōzen-ji Temple 法善寺

- (E) Higashi-Okubo Park 東大久保公園

- (F) Shinjuku Ward Office

- (G) Samurai Museum

- (I) Robot Restaurant

- (J) TOHO Cinemas Shinjuku, with Godzilla staue

- (K) Shinjuku Batting Center

- (L) Hanazono Shrine

- (M) Koizumi Yakumo (Lafcadio Hearn) Memorial Park 小泉八雲記念公園

- (N) Architecture: Sankei Building (“1 BAN KAN”)

- (O) NTT Docomo Yoyogi Building NTTドコモ代々木ビル

- (P) 椿屋珈琲店 新宿茶寮 Old fashioned Taisho-themed cafe

[…] Shinjuku Eastside Square, Fugetsudo, and the Greenwich Village of Tokyo […]

[…] Shinjuku Eastside Square, Fugetsudo, and the Greenwich Village of Tokyo […]

In 1973, I was a Chinese linguist stationed at Camp Drake in Asaka, Saitama-ken. I met my ex-wife Fukiko Hayamizu the night Fugetsudo closed. I know this because I met her with her then-husband Chris Case (now living in Chichibu) who had retrieved a tiny stainless creamer from the closing as a gift to make up for a falling out they had had earlier that day.

In the month prior to that night (my first month in Japan) I had gone to Fugetsudo a couple of times to sketch. Compared to kabukicho rock cafe I also liked called Lighthouse, it was hard to draw there because the tables were slightly low. On my second visit, I was accosted by a restless Greek who needed a crew member to help him sail a small boat to Tokyo. After going to a Shinjuku movie house to watch a movie entitled “Fear Is the Key,” we drove down to Manazuru, slept on the boat, and managed to sail the next day, entirely bypassing Tokyo Bay only to learn of our mistake upon landing on the far tip of Chiba to take on fuel. After correcting our course, we were unable in the late day to cut back across the chop of the water, and I was finally released somewhere in Chiba near a station that could get me back to town. I think all together this was a sort of Fugetsudo thing to have happen.

Fuki had been for long a “Princess of Shinjuku” in big sunglasses at all hours of the day and night, a regular for a decade of the whole Shinjuku scene. She told me that the Fugetsudo architectural design (a sort of Charles Eamesian affair) had been done by a fellow Waseda grad (in 1955?) (perhaps the son of the land owner?). Even at my late day, Fugetsudo was a center of cool hipness ( the jazz record collection along the left-hand wall as you entered was remarkably enormous) and I remember feeling stricken to learn that it had closed that night.

I have no recollection how I knew about the place to begin with.

[…] More scenes from this film: Shinjuku Eastside Square, Fugetsudo, and the Greenwich Village of Tokyo […]

[…] Shinjuku Eastside Square, Fugetsudo, and the Greenwich Village of Tokyo […]

[…] A streetcar once ran along the edge of Shinjuku’s ‘Golden gai’ bar distruct; this is now a pedestrian promenade. See: From train to tree: Golden Gai, Toden streetcar, and Shinjuku Promenade Park. And the related post: Shinjuku Eastside Square, Fugetsudo, and the Greenwich Village of Tokyo. […]